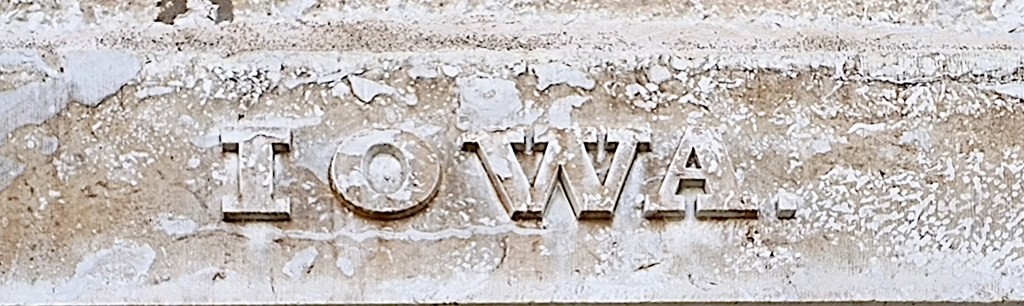

Old Capitol was built to be the seat of government of the Territory of Iowa and was the first capitol of the State of Iowa. It is now a museum that is part of the University of Iowa Pentacrest Museums. The simple inscription reading “I O W A . ” was carved in relief on two large pieces of Middle Devonian Age limestone sourced from nearby quarries and set as lintels on the east and west main entrances of the building. The period after the name had made me curious for a long time and I had decided I would research this topic further, but I didn’t move forward with it until this spring when I was prompted by Erika Bethke, an intern working with Carolina Kaufmann at the University of Iowa Pentacrest Museums, who asked if there was a reason for the dot at the end of the inscriptions on Old Capitol.

It is still a good question, one that is still hard to find a definitive answer for. After some time, it looks like the best answer is that the same social influences in book publishing also influenced the inscriptions on at least some nineteenth century buildings in Iowa City, including on Old Capitol.

How appropriate for a UNESCO City of Literature!

As it happens, there are no details about the inscription on Old Capitol in the historic record. They are not mentioned in the legislative journals, historic newspapers, or in books about the building, such as The Old Stone Capitol Remembers, by Benjamin Shambaugh or others. Margaret Keyes, an expert on Old Capitol who wrote Old Captiol: Portrait of an Iowa Landmark, included a chapter on the building’s design and construction. She did not discuss the exterior inscriptions seen above the entry doors, despite an extensive level of research on most aspects of the building. I find her to have been a detail-oriented person. I think she would have mentioned any information about the exterior lettering above the doors if it had been found. As a result, my suggestion for the best answer available is that the terminal dot in the inscriptions on Old Capitol could be explained through cultural inferences.

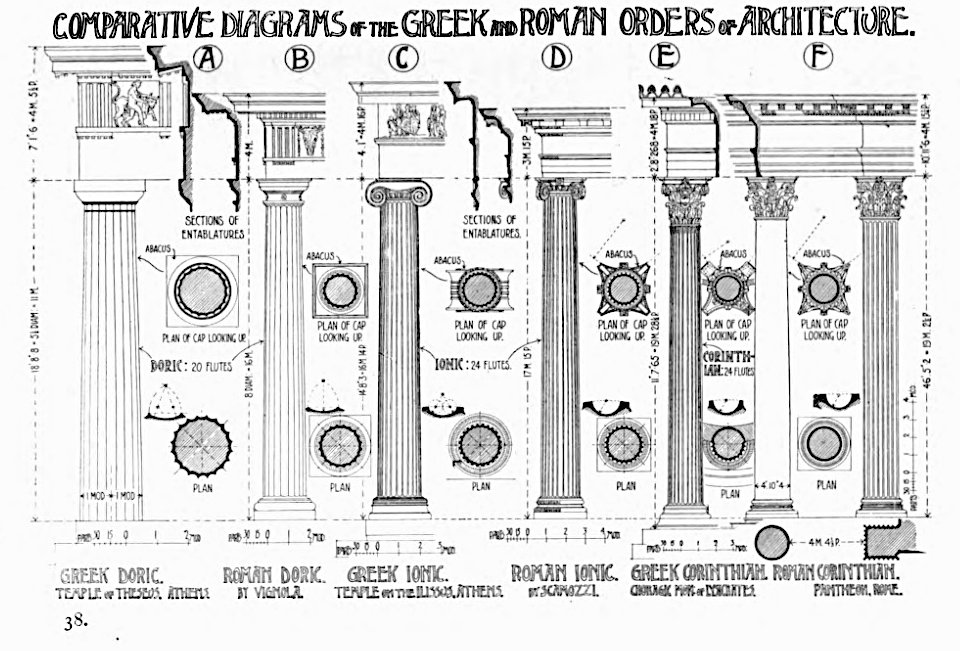

The Old Capitol was designed in the style known as Greek Revival. This style is an eclectic revival of classical architecture that combined elements of Greek Temple forms with elements from other time periods including the architectural elements of prominent buildings that were known by architects in that time, especially buildings in the Georgian style and its more restrained version known as the Federal style. Buildings in the Greek Revival style were different from their predecessors because the architects used Greek architectural orders instead of Roman. Buildings in this style in America are often called non-archaeological by architectural historians because most of these buildings were not exact replicas of Greek public buildings. Instead they were an expression of the architect’s creativity and demonstration of skill at combining a palate of traditional elements in a harmonious manner (see Roger Kennedy, Greek Revival America and Talbot Hamlin, Greek Revival Architecture in America).

But Greek Revival buildings don’t have inscriptions. Inscriptions are entirely absent from the walls of the buildings that are important precedents for American Greek Revival design, such as the Bank of Pennsylvania and the old House and old Senate chambers in the US Capitol. The bank and the rooms in the US Capitol established the use of Greek orders of architecture in America. All three were designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe and the US Capitol rooms were completed shortly before construction at Old Capitol began.

As for a possible ancient source of inspiration for the terminal dot, the convention is also missing in the historic and archaeological record of ancient Greece. In the original ancient Greek architecture, inscriptions appeared on architraves, lintels, columns, and the basement stones that formed the stylobate (see this article by Gretche Umlholtz).

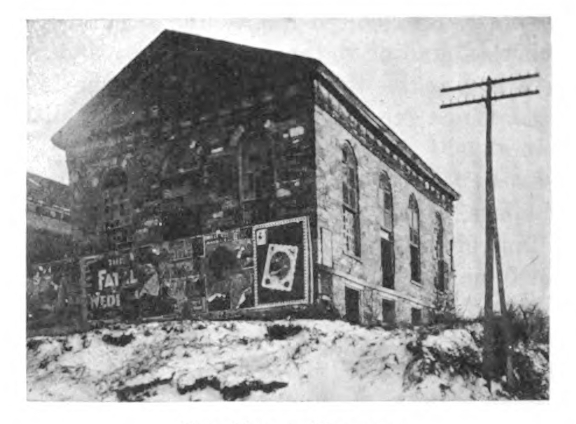

But since punctuation had yet to be invented it was absent from ancient Greek buildings. Incidentally, Romans did not use terminal dots in their inscriptions, either. With no precedent in either the original ancient Greek architecture or in Greek Revival architecture, a different explanation is required. In looking for an explanation, I tried to identify historic trends in cultural conventions in local architecture of the nineteenth century. I began by trying to find additional buildings that had also used a period or full stop at the end of an inscription. As it happens, there are a few examples that have been located in the course of researching this post. The first is a historical account that states a cornerstone was laid in 1841 on a church in Iowa City and it reportedly used the full stop format. The inscription on the lintel above the door is recorded as “Presbyterian. Erected 1845. ” (see Benjamin Shambaugh, The Old Stone Capitol Remembers, page 340). The building was the New School Presbyterian building, also known as the South Presbyterian Church, which was built even as the first phase of construction was going on at the Old Capitol. The building was likely built in part due to the Presbyterian schism following the Second Great Awakening that was about slavery as well as method of worship.

Leading Events in Johnson County, Iowa History, p. 312.

The New School Presbyterian building was located at the middle of the block on Burlington Street at about the location of the Voxman Music Building on the University of Iowa Campus, or between Clinton and Capitol streets. The inscription as given in the account uses the final dot format that the Old Capitol has. We don’t have the building or a photo with sufficient detail to confirm this today. However, the declarative period was definitely used locally in other buildings.

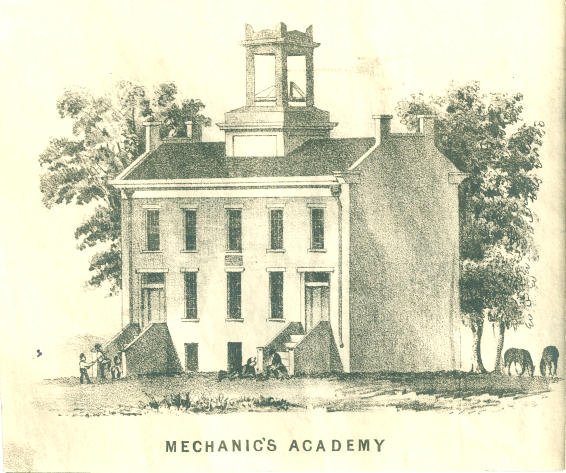

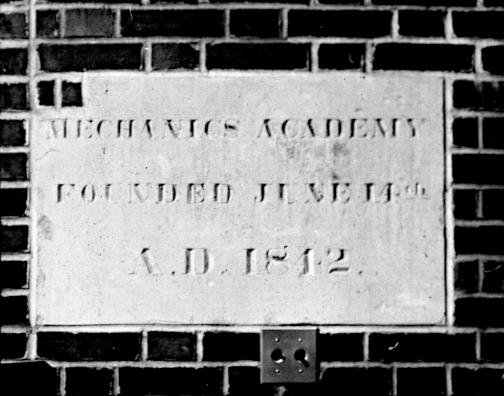

One example can be seen on the cornerstone of the Mechanics Academy building. The Inscription reads “Mechanics Academy / Founded June 14th / A. D. 1842. ” with the period included. The Mechanics Academy was built by the Mechanics Mutual Aid Association. The Iowa Territorial Legislature donated a school reserve in the capital city for the building. It was intend to host a school and library for the association, which was made up of tradespeople like carpenters, builders, masons, stone cutters and the like who were known collectively as mechanics at the time.

The Iowa State Legislature later gave the building and its lot to the State University of Iowa in the mid-nineteenth century where it was used for general instruction and the normal school, which is a school for teachers. It also was used as a dormitory which had a somewhat infamous reputation. Eventually, the building was converted into the first hospital for the University of Iowa jointly staffed by the Medical Department of the University of Iowa and the Sisters of Mercy. After the Mechanics Academy was demolished to build University Hospital, which was later known as Seashore hall and has since been demolished, the cornerstone was set in a wall at the Medical Laboratory at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine. The cornerstone that was laid in June 1842 has an inscription with the terminal dot convention. By the end of that year, the Walls of Old Capitol had reached all but the very top of the second floor, well above the inscribed lintels over the doors.

John T. McClintock slide collection on College of Medicine history

An existing building has another example of a full stop. The First Congregational Church building was built at the corner of Clinton Street at Jefferson Street in 1868, which is well after the main phase of construction at the Old Capitol was completed. A name plaque reads “First Congregational Church. ” The inscription on the date plaque reads “Erected A.D. 1868. ” and includes the full stop format. Thanks go to Erika Bethke for pointing this one out. The location of the name plaque is visible on the front face of the building on the first floor of the tower. Other inscriptions are on plaques slightly higher and on the left or north face of the tower.

A second existing building with the terminal dot convention is the 1876 Coralville Schoolhouse maintained by the Johnson County Historical Society. The date stone that reads “1876. ” is visible on the front face of the building above the second floor window.

Meanwhile, the declarative period convention followed the state capitol to Des Moines. The current capitol building uses the full stop convention on the cornerstone both after the date and after the word “IOWA. ” The cornerstone was laid in 1873.

So why did these buildings use the terminal dot with their inscriptions? As hinted at earlier, I think it was borrowed from printed books. But first, where did a terminal dot as used in Modern English and printed in books in this language come from?

A period ⟨.⟩, which is also called a full stop, is a terminal dot used as a form of punctuation that marks the end of a declarative sentence in contemporary English writing. The use of such a mark originated in about 200 BCE with Aristophanes of Byzantium, a Greek scholar at the Library of Alexandria who proposed the use of punctuation in poetry. In his system, what is known as a high dot ⟨˙⟩ was the terminal dot that indicated a full stop, or the longest pause in a text. There were also middle ⟨·⟩ and low ⟨.⟩ dots, which were intended to be used for decreasing length of pauses in the text. These are the semicolon and comma in Modern English.

Edward Thompson stated in his book An Introduction to Greek and Latin Palaeography, page 60, that the system proposed by Aristophanes wasn’t strictly followed in general practice, but it was used enough in writing that eventually medieval scribes developed and used other punctuation marks for this purpose during the eighth to ninth centuries. Over time, changes in the conventions resulted in the use of a low dot, now known as the period or full stop, which functions as the terminal dot to indicate the end of declarative sentences or statements in written texts. A survey of electronic copies of early texts online suggests the convention was in use by the early sixteenth century and given that printing in Europe began in 1455, it could not be much before that.

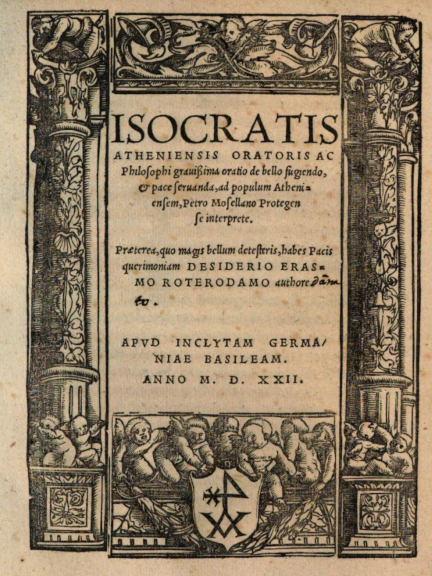

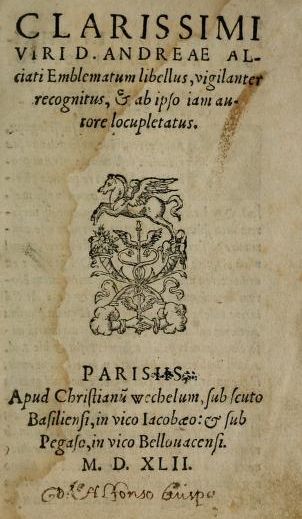

From the early sixteenth century, titles of books had periods at the end. Early book titles put a lot of information into them and often could be read as a full declarative sentence. This long form of title functioned like a table of contents in some early printed books. In the following two examples, declarative periods occur following the title, the publisher, and the date.

The first is a translation of an oration made by Isocrates against the Sophists. It was published in 1513. There are periods after each line, including title, publisher, and date.

Another example is from twenty years later. It also uses the declarative period convention. The book is commonly known as Emblamata. A translation of the title is given as Andrea Alciato’s Little Book of Emblems and contains a number of poems in Latin presented with emblems printed with woodblocks. Again, each block of text on the cover has a period at the end.

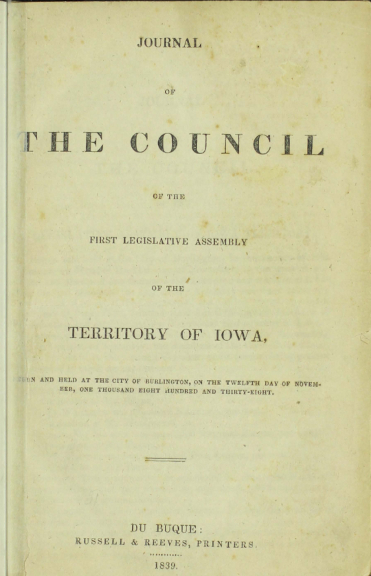

About three hundred years later in Iowa, Long titles were still common while construction of the Old Capitol building was in process. For example, the first official publications of the territory used the same format. The title of the journal for Iowa’s Legislative Council reads, Journal of the Council of the First Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Iowa, Begun and Held at the City of Burlington, on the Twelfth Day of November, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Thirty-Eight. The printer information is provided as “Dubuque: Russell & Reeves, Printers. 1839. ” with the final period included. Note the use of periods in the title, after the publisher name, and after the date. The Journal served as a form of minutes and record of things such as committee assignments, legislative actions, and directives. The Council was the upper house of the legislature.

Over time, the tradition of all-inclusive titles became less important, at least in certain publications. Some late-nineteenth century titles, especially county histories, still went on at length, and I think this was because the publishers were intentionally trying to convey a sense of authority by borrowing an older tradition for their publications. They likely were also attempting to drive up sales. But, when titles were short, so were the declarative statements that represented the title of the publication.

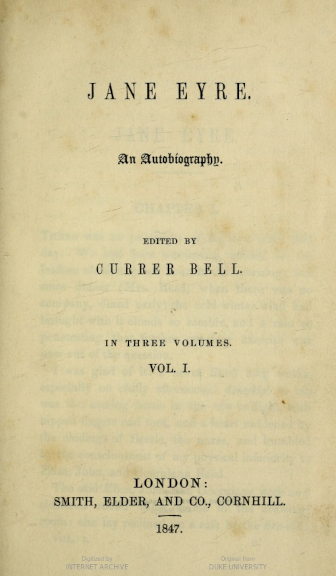

Eventually, the terminal dot appears not only after titles and dates, but also names, subtitles, volume numbers, and such. A first edition of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre displays what today looks like all kinds of extra periods even in short phrases such as the editor’s name. Every element on the title page has a period after it, seemingly turning it into sentence.

Note that the editor’s name is the pseudonym that Bronte published under due to her gender and the restrictions on women publishing their work. It’s not clear why the use of additional periods was done, but it feels like it was done for emphasis, as in a formal declaration.

Locally, printed materials other than books also followed the use of periods. Gerald Manshiem presented a photo of a social invitation that is in the collections of the State Historical Society of Iowa in his book, Iowa City: An Illustrated History, page 41. The invitation announces a “Cotillon Party. ” [original spelling] that was to be held on New Year’s Eve, 1849. The invitation is signed “MANAGERS. ” It is dated “Iowa City, December 29th, 1849. ” and every statement has a terminal period.At least one other inscription made shortly before the Old Capitol was built also used this format. As reported by Charles Negus in the Annals of Iowa, page 326, the original plank of wood driven into the ground to declare the future location of the territorial capitol at Iowa City was inscribed as follows.

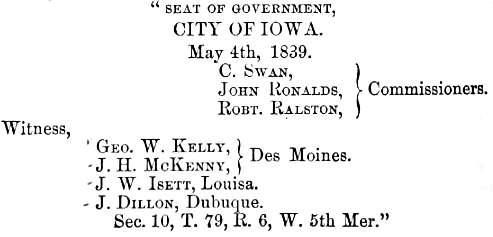

“Seat of Government, City of Iowa. May 4th, 1839. C. Swan, John Ronalds, Robt. Ralston,: Commissioners. Witness, Geo. W. Kelly, J.H. McKenney,: Des Moines. J.W. Islett, Louisa. J. Dillon, Dubuque. Sec. 10, T. 79, R. 6, W. 5th Mer.”

The inscription gives the names of the three commissioners along with the names and counties of four witnesses. It concludes with the physical location of the section of land claimed for the capitol as notated in the format of the Public Land Survey System, which says “Section 10 of Township 79 North and Range 6 West of the Fifth Principal Meridian.” As in other places, all items in the transcription had a declarative period even where they currently seem exceptionally unnecessary.

Since the article giving these details was published in 1869, it could simply be that the editor of Annals of Iowa at that time chose to have the type set in the format that matched the contemporary style which was to use declarative periods, but the format does not seem like one that would have been a first choice for an editor to make. In either case, it goes toward my point that in the nineteenth century people of Iowa used terminal dots somewhat freely in formal contexts, even if on a plank of wood set into the ground on the frontier.

As another example of the terminal dot in common printing, let’s take a look at the masthead of the first year of the University Reporter, a forerunner to the Daily Iowan that ran from 1868 to 1879. It and other titles were published by the University with student writers. The masthead continued to use the declarative periods throughout its run and the convention continued with the run that followed, which was named the Vidette–Reporter. Every Element is followed by a period from title, to place of publication, the name of the university, the motto, volume number, issue number, and date.

So many periods.

So, my thoughts are that the convention of a full stop on the buildings in Iowa City followed the drafting of the plans for Old Capitol and when they were viewed by the Legislature in December 1839. It is not a convention that comes normally in Greek Revival architecture, has no precedent in ancient Greece, and it is also not a usual practice of John Rague, the architect of the Old Capitol. This is the only of his buildings that I found with an inscription (see Betsy Hathaway Woodman, “John Francis Rague: Mid-Nineteenth century Revivalist Architect (1799–1877),” M.A. Thesis, University of Iowa, 1969.” Therefore, it is seems probable the inscription on the Old Capitol was added on the direction of Chauncey Swan, the Acting Commission of Public Buildings for the Territory of Iowa or less likely on the initiative of the stonemason who was doing the decorative work at the time the lintels were dressed and made ready to install.

And so, to answer the question of why there is a terminal dot following the inscription on Old Capitol, I suggest that it was intended as a declarative period, that its usage was borrowed from the printer’s conventions of the time where single words could be treated as a whole sentence. Even as Old Capitol was being built, the leaders of the territory were already aspiring to be a state. I think the usage here is due to a need to convey a sense of purpose and authority. A period is normally functional, but here it may have conveyed additional meaning to the people of its time. I think it was a succinct title that was intended to indicate formality, even if it was actually a bit architecturally colloquial in its use. With poetic license, and including the terminal dot, the inscription seems to say,

I O W A .

This building was built for The People of Iowa.

It represents the body politic,

A democratic electorate,

Who are Iowa.

________

Note: In an effort for better clarity I have used an unconventional convention when quoting examples of inscriptions, either with or without a terminal dot. It is an open style with a trailing space before the closing quote mark. In these instances, periods used to conclude a sentence are outside the closing quote mark.

Note: For this article I have set aside the problematic nature of the early Iowa culture when only white men could elect its members and the prevailing racism of the time based on their legislative record and statements made by editors of the newspapers of the time. This is a topic I hope to address in print, but if not, look for it in a future post here.

Acknowledgement: I was fortunate to be asked to be part of a panel discussion of the building’s history and architecture as part of a series of talks related to an exhibition in the museum in 2022 and asked back to speak to University Staff about the architecture and the process of building the Old Capitol. This past spring, I had the opportunity to talk with Erika Bethke, an Intern at the University of Iowa Pentacrest Museums. We chatted about the architecture of some of the key buildings on campus. I thank her for the research prompt that pushed me to do the research to finish this post and also for looking for additional photos of buildings using the terminal dot format.