Just north of the central business district of Iowa City stands a red church building known as Old Brick. It was built in the middle of the nineteenth century at the corner of Clinton and Market Streets and now sits adjacent to the present University of Iowa Campus. Old Brick was constructed in an eclectic Romanesque revival style. Revival in architectural history refers to the re-introduction of a style. Revival styles typically add aesthetics from the contemporary cultural milieu to one or more earlier architectural styles. The round arches over the windows and in the belfry section of the tower evoke ancient Roman architecture as does the gable end of the roofline, forming a pediment.

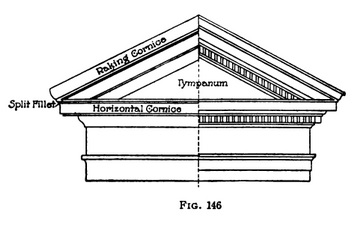

Pediments are seen in the triangular end of the roofs of temples of Classical antiquity and as well as in revivals of that based on that time period. They eventually were used as ornaments above doors and windows as well as the gable ends of buildings.

The design of Old Brick is also eclectic in that its design references several previous styles. Among these styles are the European revival of Roman architecture, especially in church buildings, known as Romanesque. For this reason, there are some details that hearken back to European buildings built during the Norman Romanesque period. Another style that is borrowed here is the Gothic period of the Middle Ages. Gothic architecture was almost exclusively used in church buildings. The elements that the designers of Old Brick borrowed include the massive wooden front doors with quatrefoil windows as well as the decorative woodwork in the main hall. Both Norman and Gothic churches used stained glass.

Additionally, the massing of the building in the form of a large rectangular section capped in a peaked roof but the angle of the roof is determined by the pediment rather than a steeper angle found on many churches. Old brick also features a relatively massive tower at the front of the building, something seen on many Norman churches. As the National Register Nomination Form points out, this specific type of floor plan is also common among early nineteenth century churches in New England. Churches in the Northeast were heavily influenced by English churches of the Enlightenment during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that were designed by Christopher Wren, James Gibbs, and their contemporaries. It is worth noting that this design was also was common in Iowa from the 1830s and later.

The foliate stained glass designs in the windows evoke Celtic interlace designs, or knotwork, likely a reference to the Scottish heritage of the Presbyterian sect of Christianity that was brought to America by Scottish immigrants. However, the background of Presbyterian Church membership was typically much more diverse in terms of ethnic heritage. The proportion of Scottish people in Iowa City remains low throughout history based on census data.

In keeping with the image of New England churches, Old brick formerly had a tall spire. That steeple was destroyed in the July 1877 derecho. The contemporary University of Iowa professor Gustavus Detlef Hinrichs is recognized as the first to identify this unique weather phenomena from data gathered across Iowa from that storm. A portion of the square tower on Old Brick was also damaged in the high winds. When rebuilt, the building featured its current crenelated parapet, further evoking churches of the English Middle Ages.

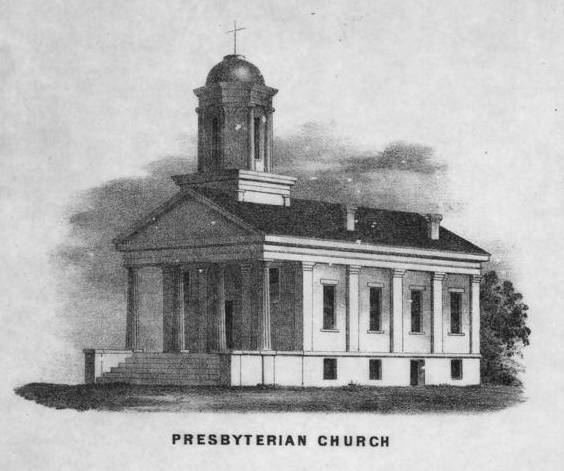

The previous First Presbyterian church was brick clad like the current Old Brick building, but looked substantially different than the current building. It has been described in histories as similar to the contemporary Baptist Church building. A fire caused by a spark from a steam mill destroyed the wooden portions of the building in 1856.

Construction of Old Brick began that same year but proceeded only slowly. This was caused by a number of factors including funding, labor, and materials shortages. The removal of the capital of Iowa to Des Moines in 1857 reduced the number of church members and social functions that were reported to occur as part of the Church. This would have reduced donations for construction costs. Further, the Civil War slowed the progress of construction. Labor shortages were as likely as materials shortages to have caused this. The war shifted the labor of craftspeople, likely all men, to the Army. Transportation constraints were also likely a problem. Rail and riverboat traffic were prioritized for the war effort. Nails, sheet metal, and stained glass had to be shipped to Iowa City from the same industrial centers that had retooled for making guns (cannon), side arms, ammunition and the like. Transportation was reassigned to moving troops, supplies, and relocating freed Black people to the upper Mississippi valley from the battlefront. Old Brick was finished just after the war ended with the dedication occurring in August 1865. It was not the first brick building in Iowa City, and is not by any stretch in the oldest of the community’s buildings. Several residences are older, dating to the 1840s and 1850s. But, Old Brick remains the oldest surviving church building and is worthy of preservation due to its architecture and association with events in Iowa City’s history.

Old Brick was constructed for the First Presbyterian Church. The congregation of this church organized in Johnson County by Autumn of 1840 as the first Presbyterian congregation in Iowa City. As a result, their buildings and congregations, for which there have been several over the years, are also known as First Presbyterian. The congregation also appears in histories as the North Presbyterian Church, a member of the Old School party of the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. For historical interest, it’s worth exploring the epithet “Old School” in at a little more detail. There was a schism in the Presbyterian sect of Christianity in the United States that began around 1830 resulting in conservative and revivalist factions. These were known as the Old and New School Presbyterians. The differences between the old and new were theological, especially concerning the Liturgy or manner of worship. The original First Presbyterian Church, Iowa City, separated along these lines in 1852. The congregations became the North Presbyterian and South Presbyterian Churches. The north building, the original First Presbyterian at Clinton and Market Streets, was affiliated with the Old School while the south building, formerly located on Burlington Street approximately where Voxman Music Building is today, was affiliated with the New School. The New School was aligned with religious revivalism, camp meetings, and participated in the larger sphere of society known as the Second Great Awakening. This theological movement held that individual behavior, including strict moral comportment and temperance as well as emancipation for all people, Black or white, would lead to salvation of society as a whole. Emancipation of Black people was still seen as politically radical. The Old School remained more traditional and noncommittal on emancipation, the moderate or popular position in the United States North at that time. The South Presbyterian Church, sometimes called the Old Stone Church, was sold following the reunification of the two congregations in 1870. At one time the State Historical Society was housed there.

It’s not clear with the current level of research what role the individuals that were members in the First Presbyterian Church played in the major change in Iowa’s attitudes toward involuntary servitude (slavery) that occurred in the decades leading to the Civil War, but since the second building, today’s Old Brick, was not completed until after the end of the Civil War and the limited writings on this period indicating that the congregation met in other places during this time, Old Brick likely played no great part in events surrounding the war or its related events and movements. Incidentally and much later, Professor Samuel Calvin, a Scottish-born geologist, was a member of the church and he took some of the first aerial photographs of Iowa City from the top of the crenelated tower.

Old Brick is more than a symbol of Nineteenth Century architecture and church history. Importantly, Old Brick is also the living record of the modern historic preservation moment in Iowa City. In the Friends of Historic Preservation’s twenty-fifth anniversary history, the saving of Old Brick from demolition is shown to be the major factor that led to the founding of their group as well as the catalyst for the historic preservation movement in Iowa City. In the late 1960s, The Church and its building was under new leadership and looking toward a different direction. Iowa City was undergoing urban renewal and demolition of old buildings was very common. Although highly controversial, the appeal of new buildings and new subdivisions was then probably was at its greatest peak that it had been since the major expansion of subdivisions, known then as land additions, that occurred shortly after 1900 and continued into the early decades of the twentieth century. Despite the name “addition,” most were built outside the city limits. Iowa City held a referendum to expand the city limits to include the new land additions around 1910, and thus secured additional tax revenue for services the City was apparently already providing.

In the late 1960s, a majority of the members of the First Presbyterian Church voted to move to a new location outside the edge of the built-up area of town in a new subdivision. To facilitate the move, a majority of members of First Presbyterian decided to demolish the Old Brick building to aid in finding a buyer for the property. The suggestion to demolish Old Brick had wide effects. In a series of events worthy of a novel or movie adaptation, a story unfolded in the local, state, and national press. There were many players involved, including multiple parts of the state government often working across purposes. University professors, the university administration, the Board of Regents, The Iowa Division of Historic Preservation, as well as members of two church congregations and other members of the Iowa City community organized into one of three different groups: Those for demolition to sell the land to the highest bidder, those to retain the building as a consecrated church, and those to preserve it in any manner possible. All played a role and almost everyone involved ended up with mud on their face at one point or another.

A contingent of University faculty and members of the public pressured the University to step in to prevent demolition of Old Brick. It was thought the University had the resources to purchase the property and this would buy time to figure out what could be done with the building after the Presbyterians left it. The university administration first made a public overture to preserve the building as as a Church. However the Lutheran congregation that was interested in the building were blocked from the purchase at a higher level in their organization. The University of Iowa administration next became politically ensnared in the when they offered to, and the Regents approved of, the purchase of Old Brick in 1974 for their own use, which was likely to be a parking lot. It is worth noting that the major restoration of Old Capitol was ongoing, as was demolition of mostly vacant buildings downtown.

Church members began to remove materials from the building and sell them prior to demolition. This likely was equal parts of not wanting to loose the more decorative parts of the building to the landfill but also a financial expediency. A Church building a new facility is likely to need cash on hand, so thrift could have been seen as necessary. The missing stained glass windows in the main hall of the building is due to this course of action.

A grassroots organization formed the next year adopting the name Friends of Old Brick, or originally Friends of the Old Brick Presbyterian Church. The effort to preserve the building was led by members of the church, including Dorthy Whipple and Emil Trott, an affluent lawyer. Joseph Baker, an English Professor, and Tillie Baker were other members of Friends of Old Brick and had formerly been members of First Presbyterian Church. They had been excommunicated in 1968 after they actively campaigned in opposition to the sale of the building.

The Bakers felt like the process of making the decision to sell was not completely above board. Their offense evoked the Reformation. They nailed a set of grievances to the church door in 1967 at the time that demolition and the sale of the lot was being considered by the congregation. Subsequently, Tillie worked with university faculty, some who were in the UI School of Art and others in the department of Architecture at Iowa State University’s College of Engineering, to nominate the building to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. Needing someone to occupy the space, the Iowa Division of Historic Preservation, then located in Iowa city, moved into the building, preventing demolition for the time being.

Friends of Old Brick, with the help of the Iowa Department of Historic Preservation and a group of lawyers and citizens who were separate from Friends of Old Brick, forcefully persuaded the university administration to sell the building rather than raze the building for a parking lot. The Regents at first refused the sale of the building to the grassroots preservation organization, however a sustained campaign of letters to newspapers and threats of law suits changed their mind. Ultimately, an Episcopalian Church agreeing to save the building was approved to buy the property, and here we are.

The effort to approve the eventual sale and preservation of Old Brick outlines many factors involved with high-profile preservation cases. Historians, architectural historians, and art historians can nominate a building to the National Register, but that is a lengthy process, requires approval at several levels, and holds no force to prevent demolition for anything except Federal projects, grants, assistance, and permits, collectively known as “undertakings.” To preserve a building often takes financing and legal advice to complete the process and occasionally, as in this case, a healthy amount of publicity to change political will. Since the time that Old Brick was saved, Iowa City has created a local ordinance that allows buildings and districts to be nominated as locally significant historic resources using a zoning overlay zone to require review prior to major modifications and demolition.

Today, Old Brick is operated by the Episcopal Diocese of Iowa. It is a good example of adaptive reuse. The main hall, the former sanctuary, serves as a non-sectarian events space for weddings and other functions. The former classrooms and offices serve as low cost rental space for non-profit organizations, an incubator. Renters include the Housing Trust Fund of Johnson County.

_______

Note: For disclosure, my parents were married in Old Brick and they raised me in a Presbyterian Church in Marshalltown, Iowa. Most of my relatives in Iowa City attended the First Christian Church, formerly located on Iowa Avenue. I was inspired to write about Old Brick after the grassroots effort to save several Civil-War era buildings was launched a few years ago by Friends of Historic Preservation. tsw

For more information

Old Brick website https://oldbrick.org/

Friends of Historic Preservation https://www.ic-fhp.org/about

Sources

Clarence Ray Aurner, Leading Events in Johnson County, Iowa History. Volume 1. Cedar Rapids, IA: Western Historical Press, 1912, pages 311–322

Clarence Ray Aurner, Leading Events in Johnson County, Iowa History. Volume 2. Cedar Rapids, IA: Western Historical Press, 1913, pages 366–367

Mrs. Joseph E. “Tillie” Baker, North Presbyterian Church. National Register Nomination Form ID 73000730, Washington, D.C.: Keeper of the Register, National Park Service, 1973

Daily Iowan, Nov. 23, 1967, page 1

Daily Iowan, Jan 1, 1974, page 1

Iowa City’s Friends of Historic Preservation: Their First 25 Years. Iowa City: Friends of Historic Preservation, 2001, pages 2–8

Joseph Hubbard. The Presbyterian Church in Iowa, 1837–1900: History. Cedar Rapids: Committee of Synod of Iowa, 1907, page 3

Leslie A. Schwalm, Emancipation’s Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest, Chappel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009, pages 81–106

Lowell J. Soike, Necessary Courage: Iowa’s Underground Railroad in the Struggle Against Slavery. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2013, pages 9–10