The land that is the United States today was turned over to the US Government in a series of federal legal actions beginning in the 18th century and continuing into the 20th for Alaska and Hawaii. Some 368 treaties, laws, and executive orders totaling around 1.5 billion acres of land conveyed right of ownership from indigenous peoples to the federal government, and eventually to private hands. Euro-Americans—Americans of European and especially white descent, primarily benefited from these transactions. This has had a tendency to erase indigenous peoples from the conventional wisdom of Iowa history as seen by white culture.

Tracing the indigenous people who have inhabited Iowa over the past is a complicated matter. Any effort to list each tribe is fraught with difficulties. Oral traditions are often discounted by the government. Traditions can also differ in interpretation from other forms of evidence. The fluid nature of land use by most Native Peoples due to their lack of permanent settlement and the arbitrary nature of state boundaries and the Euro-American concept of property ownership hasn’t helped keep the record straight. The use of Iowa post-contact as an area to place peoples who were removed from further east, much like many Great Plains states (especially Oklahoma), later created other issues especially as tribes assigned to live here or to be removed were not always willing to comply on an individual or tribal basis.

Today there is one official tribe located in Iowa and they are the Meskwaki, known to the US Government as the Sauk and Fox of the Mississippi in Iowa. The Meskwaki actually purchased their settlement near Tama, Iowa from the government rather than receiving it as a concession for a treaty agreement. The Euro-American court system took some time to sort out if they would consider that transaction legal or not.

Traditional public educational efforts have taught there were five tribes historically associated with Iowa: the Ioway, the Sac and Mesquakie [French spelling], the Winnebago, and the Pottawattamie. These tribes are alternatively known as Báxoǰe, Suak (oθaakiiwaki), Meskwaki (Meshkwahkihaki), Ho-Chunk or Winnebago, and Potowatomi (Neshnabé). But 48 Native American groups —tribe, band, or nation—listed by the federal government consider Iowa to have ancestral associations to them.

Iowa Native American Lands in US Treaties and Laws

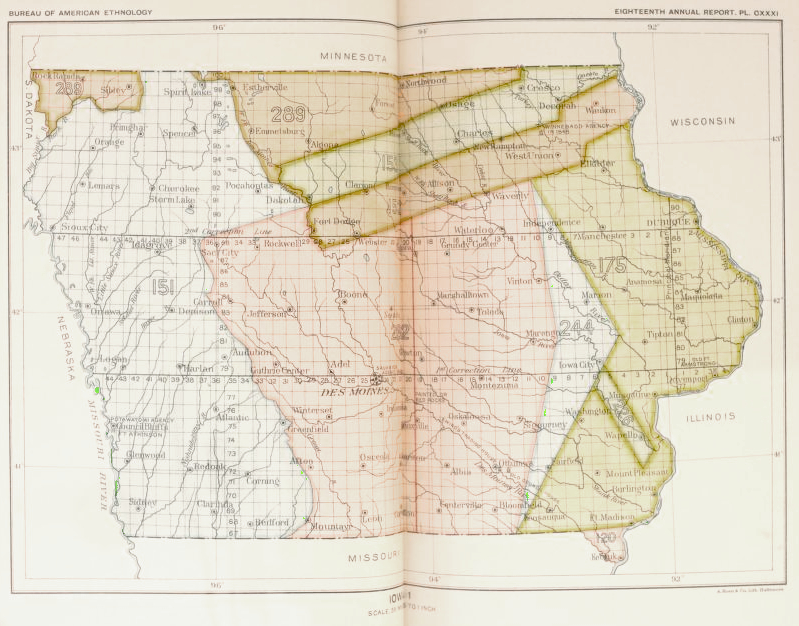

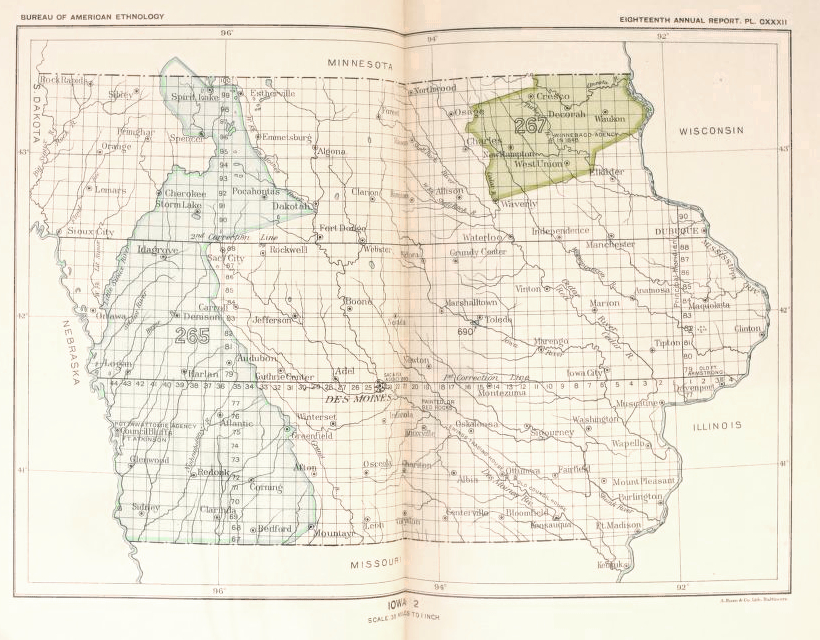

Charles C. Royce and Cyrus Thomas attempted to provide order to the flurry of US land acquisitions and other treaties through the time period 1774 to 1894 in the nearly 530-page second volume to the Eighteenth Annual Report from the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The book provides a treaty schedule and concordance maps printed on color plates. Unhelpfully, the authors standardized tribal names to their own liking from what was written in the actual treaty. The Smithsonian library provides an excellent facsimile of the volume here and high quality scans of the maps are also available online at the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress American Memory Project has a now very dated web site that still provides a helpful list of treaties by state, tribe, and year.

Twenty treaties directly affected tribes who claimed land in Iowa of which 16 affected land in Iowa. Some of these treaties occurred after Iowa was a state, but most were previous to that date (December 28, 1846). Land cessions in the upper Mississippi River basin began as early as 1795 with the Treaty of Greenville in which a sweeping treaty cleared much of Ohio for settlement but also reserved several military posts in Illinois to the US Government. Nine years later, the Treaty of St. Louis agreed the combined tribes Sauk and Meskwaki, or Sac and Fox in the official wording of the government, would cede much of the northeast quarter of Missouri, the southwestern corner of Wisconsin and the northwest third of Illinois. The Sauk and Meskwaki officially were supposed to move into Iowa, which has been reported to have been an area for annual hunts previous to this. There are indications this was done to an extent. But other tribes would have been in Iowa at that time, especially Ioway, Otoe, Omaha, and Ho-Chunk/Winnebago and various Dakota tribes frequented Iowa for hunting grounds and didn’t appreciate more competition. The 1804 treaty was reasserted in 1815 and 1816, indicating the Sauk and Meskwaki were not taking much notice of the original agreement that was probably made in less than legal circumstances. Five representatives who had been sent to St. Louis to negotiate a prisoner release, not to sell land found themselves being asked to sign agreements it is thought they did not have authority to make, did not fully understand what was being agreed to, and possibly were in no condition to be making such negotiations. It has been asserted this lead to a disagreement that helped bring on the Black Hawk War.

In 1824, the Sauk and Meskwaki ceded their remaining interest in Missouri. Two decedents of “mixed-race” parentage, Maurice Bondeau and a man named Morgan, requested that a so-called Half-Breed tract be set up for “mixed-race” decedents of native women whose fathers were said to be Scottish, but likely also included French and Spanish, farmers, traders and miners, and merchants. Euro-American and Native couples had existed in the French and Spanish Louisiana district at places such as Dubuque, Davenport, Ste. Genevieve, Kaskaskia and St. Louis beginning more than a hundred years earlier in 1703. Bondeau and Morgan’s request was granted and a triangular area between the Des Moines River and the Mississippi extending around 1.5 miles downstream from Farmington, Iowa to Keokuk then up the Mississippi to Ft. Madison and back to the starting point became officially the Sac and Fox Reservation—the so-called Half-breed Tract, but no individual right to land titles existed. Subsequently, Congress enacted the right to reverse the title contained in the original treaty and separately appropriated $1,000 to survey the tract. Supposedly this law was sponsored due to a request of those living in the tract who desired to be able to own parcels of land, but it seems equally likely from the outcome that land speculation companies could have been at work. In any event, the area was opened for settlement in 1834 just two years after the first Black Hawk Purchase in 1832.

Iowa 1, Royce, Charles C., and Cyrus Thomas, Indian Land Cessions in the United States, Eighteenth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Plate CXXXI (131)

Iowa 2, Royce, Charles C., and Cyrus Thomas, Indian Land Cessions in the United States, Eighteenth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Plate CXXXII (132)

In 1825, an invisible demarcation line was optimistically and unrealistically made to separate principally the bands of the Santee Dakota from the Sauk and Meskwaki who were now in Iowa, though several other tribes were included in that treaty. It was intended to be a hard border but it was not enforced. Five years later a Neutral Ground was created to reinforce the demarcation line in 1830. The Ho-Chunk/Winnebago were then moved into this area in 1837 with a military presence ostensibly intended to keep the peace through threat of force

Four years previously, the Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi had been officially moved to western Iowa in 1833. Ten more treaties cleared the way for settlement in Iowa from 1832 to 1851. The dates and salient details are provided in the table below.

| Date Signed | Tribes | Description | Royce Map Reference |

| Aug 4, 1824 | Sauk and Fox and descendants of mixed ethnicity | Sac and Fox Reservation (the so-called Half-Breed Tract). The tract was created in the following provision of a land cession in Missouri, “It is understood, however, that the small tract of land lying between the rivers Desmoin [sic] and Mississippi, and the section of the above line between the Mississippi and the Desmoin, is intended for the use of the half-breeds belonging to the Sock and Fox nations, they holding it, however, by the same title and in the same manner that other Indian titles are held.” Treaty made at Washington, D.C. | 120 |

| Aug 19,1825 | Sauk and Meskwaki, and several bands of Santee Dakota including Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Wahpeton, and Sisseton along with Ioway, Otoe, and Missoria and Mamaceqtaw (Menominee). |

First Treaty of Prairie du Chien. Demarcation line running in the middle of the what was to become the Neutral Ground. The treaty was was largely, if not entirely, ignored by the Sauk and Meskwaki and the Santee Dakota. Article I provided the following rights, “But it is understood that the lands ceded and relinquished by this treaty are to be assigned and allotted under the direction of the President of the U. S. to the tribes now living thereon or to such other tribes as the President may locate thereon for hunting and other purposes.” | |

| Jul 15,1830 | Sauk and Meskwaki, and several bands of Santee Dakota including Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Wahpeton, and Sisseton along with Ioway, Otoe, and Missoria tribes. |

Formation of the Neutral Ground, cession land in western Iowa, southwest Minnesota, and Northwest Missouri. Treaty made at Prairie du Chien. Royce Map Reference 69 was an 1824 cession for area in Missouri which repeated providsions of a treaty signed on August 19, 1825 | 152, 153, and 151 |

| Sep 15, 1832 | Ho-Chunk / Winnebago | The Neutral Ground was made available for voluntary relocation and partial title to Wisconsin ceded. The treaty was made as part of the terms for the Black Hawk War at Fort Armstrong, Rock Island | 151, 152 |

| Sep 21, 1832 | Sauk and Meskwaki | Black Hawk Purchase at Ft. Armstrong, Rock Island as part of the peace treaty to end the Black Hawk War. This agreement also created Keokuk’s Reserve | 175, 226 |

| Sep 26,1833 | Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi | Treaty of Chicago. Affected tribes were relocated to western Iowa. This tract was ceded June 5, 1846 | 265 |

| Jun 30, 1834 | Sauk and Meskwaki and their descendants | Sac and Fox Reservation (the so-called Half-Breed Tract) opened for settlement. Acts of the Twenty-Third Congress, Chapter 167, “An Act to relinquish the reversionary interest of the United States in a certain Indian reservation lying between the rivers Mississippi and Desmoins.” Passed both houses of Congress January 30, 1834. | 120 |

| Sep 28,1836 | Sauk and Meskwaki, Ioway | Keokuk’s Reserve. Treaty titled, Sauk and Fox at the treaty ground on the right bank of the Mississippi River, in the County of Dubuque and Territory of Wisconsin, opposite Rock Island. The Ioway held claim to a portion of the reserve and this treaty set up the meeting that took place in 1837 where the Ioway presented their map to the US Government to establish their past land use in the upper Mississippi valley. The Iowa District of the Wisconsin Territory had two counties, Du Buque [sic] to the north and Desmoine [sic] to the south. | 226 |

| Oct 21,1837 | Sauk and Meskwaki | Second Black Hawk Purchase and revocation of rights granted in Article I of the 1830 Prairie du Chien treaty. This took place during the 1837 treaty meetings in Washington, D.C. | 244, 151 |

| Nov 1,1837 | Ho-Chunk / Winnebago | Cession of all land east of the Mississippi and relocation from Wisconsin to the Neutral Ground. This took place during the 1837 treaty meetings in Washington, D.C. The right to occupy the east half of the Neutral Ground was also ceded. | 267, 151, 152 |

| Oct 19,1838 | Ioway | All right or interest in the country between the Missouri and Mississippi rivers (Northwest Missouri was ceded in 1824, Royce Map Reference 69). This cession made as a result of the 1837 treaty meetings in Washington, D.C. Earlier partial cessions in Iowa had been made but were essentially disputed in 1837. | – |

| Oct 11,1842 | Sauk and Meskwaki | Cession of all land west of the Mississippi to which they claimed title with the following provision, “The Indians reserve a right to occupy for three years from the signing of this treaty all that part of the land above ceded which lies W. of a line running due N. and S. from the painted or red rocks on the White Breast fork of the Des Moines river, which rocks will be found about 8 miles in a straight line from the junction of the White Breast with the Des Moines.” Treaty made at the Sac and Fox agency [Agency, Iowa]. | 262 |

| Jun 5,1846 | Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi | Cession of land provided in Treaty of Chicago | 265 |

| Oct 13,1846 | Ho-Chunk / Winnebago | Neutral Ground cession | 151, 152 |

| Jul 23,1851 | Wahpeton, and Sisseton bands of Santee Dakota | Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. Cession included all lands in the State of Iowa and eastern Minnesota. | 289 |

| Aug 5,1851 | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute bands of Santee Dakota | Treaty of Mendota. Same terms as the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. | 289 |

Resources for Further Interest

Acquisition of Iowa Lands From the Indians. The Annals of Iowa, volume 7, number 4, pages 283–290, 190. https://doi.org/10.17077/0003-4827.3259

Royce, Charles C., and Cyrus Thomas. Indian Land Cessions in the United States. Eighteenth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1896-97, by J. W. Powell, Director. Part 2, pages 521–964, plates CVIII-CLXXIV, Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 1897 https://repository.si.edu/handle/10088/91692

Sherman, Bill. Tracing the Treaties: How they affected American Indians and Iowa. Iowa History Journal http://iowahistoryjournal.com/tracing-treaties-affected-american-indians-iowa/

Swierenga, Robert P. The Iowa Land Records Collection: Periscope to the Past, Books at Iowa volume 13 pages 25–30, 1970 https://doi.org/10.17077/0006-7474.1320

Notes

- This post was updated in December 2023. See the companion post on maps of Native nations here.

- One of my graduate assistant duties in the early 1990s was to assist Professor June Helm teach her North American Indians course in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Iowa.

Really enjoyed reading about this history. I’d like to know more about where your office has found artifacts and are there any ongoing digs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Neva. I’m no longer at the OSA. There is a fair amount of information online at their website. https://archaeology.uiowa.edu . You can reach out to them through Education Assistant Cherie Haury-Artz who has contact information at https://archaeology.uiowa.edu/education . You can also try to link up with a local chapter of the Iowa Archeological Society, https://iowaarcheologicalsociety.org . There are museums around the state that have various levels of programming as well. Iowa Hall at the University of Iowa, the State Museum in Des Moines, the Putnam Museum in Davenport, and the Sanford Museum in Cherokee are some examples. The Meskwaki also have a museum at their settlement near Tama. There are also a number of public sites you could visit, such as Toolesboro Mounds State Historic Site near Wapello, and Effigy Mounds National Monument near McGregor. Ask Cherie for more details!

LikeLike

Hi Tim. I live north of Decorah, IA, slap bang in the middle of the Neutral Ground. Discovering this led me to investigate the Winnebago removals from Wisconsin and that has become a burgeoning project on the scale of Royce and Thomas. I should have started organizing my research files earlier . . . as I now have an unwieldy mountain of data that is slowly being added to a spreadsheet.

I have a question: have you any information (or view) regarding the translation and recording of the pre-treaty council meetings. We know who the interpreters were, but what was the process. I wonder how much was lost in translation? For example, Caleb Atwater’s account of Little Elk’s speech at Prairie du Chien in 1829 is a greatly embellished from the official record. (Atwater had a habit of doing that.)

David

PS Re. your post on Robert Owen, I lived for many years near Newtown, in Wales, his birthplace and home to the RO Museum!

LikeLike

Hi David.

Thanks for your comments. Your research sounds interesting!

I’ll try to answer your question about how complete the historical record is for what took place at treaty negotiations.

Based on undergraduate courses and some reading since, I know that the treaty negotiations were intended to favor US interests. Any consideration for native interests would have been secondary to this.

There was at least one treaty that later was disregarded because of the process followed. The US negotiator conducted negotiations with individuals not authorized by their leaders to sign a treaty and the negotiator likely gave the native individuals enough alcohol that they couldn’t make rational decisions. So the events of each negotiation should be looked at carefully.

The official process and history of treaty negotiations is described at this page of the National Archives and Records Administration website. https://www.archives.gov/research/native-americans/treaties.

But more subjectively and anecdotally, the record of an official proceeding rarely is as detailed as a modern court record or a modern transcript. So someone has interrupted what took place and what was thought to be important to write down. Some level of detail about the events would have been lost. And without diaries or interviews, it’s not possible to know what everyone was thinking and what their exact rationals were. Other documents and studied interpretations can help fill in the gaps.

Good luck with your work on the neutral ground! The Office of the State Archaeologist at the University of Iowa may have additional resources you haven’t considered.

LikeLike

Tim, thanks for your reply. You maybe referring to the 1837 treaty in Washington where there were not enough Bear Clan members present with authority to sign and they were mislead in to thinking they had eight years to move instead of eight months. Or the 1853 treaty which was never ratified.

“Special List No. 6” is a valuable source of information and the related correspondence reveals the true intentions of those involved as do congressional records of debates.

I’ll keep searching for clues.

David

LikeLike

It sounds like you have some good leads. So, that treaty that the Sauk and Meskwaki didn’t authorize was the one negotiated by William Henry Harrison at St. Louis in 1804. It didn’t cede land in Iowa.

LikeLike